Beverly Cleary, Ramona, my mother, and me

Remembering an amazing author on the occasion of her birthday (or close enough)

The best children’s stories transport us back to our own childhoods. The truly transcendent ones do more than that — they have the power to telescope our lives and our memories such that, for just a moment, we can see as both young and old; as both the parent and the child. No one wielded that power more powerfully than Beverly Cleary, whose 107th birthday would have been last week.

Cleary, who lived to the remarkable age of 104, was feted in life with many remembrances, including numerous awards, at least one Senate resolution, and a sculpture garden depicting some of her most memorable characters.

Like thousand of other kids, I grew up reading Cleary’s books, and always found something in them that spoke to me. As a kid growing up in Oregon, it was special to me that Cleary, too, was an Oregonian; I devoured her autobiography as a young kid and delighted to think that the places that shaped her childhood were a short drive away from my own.

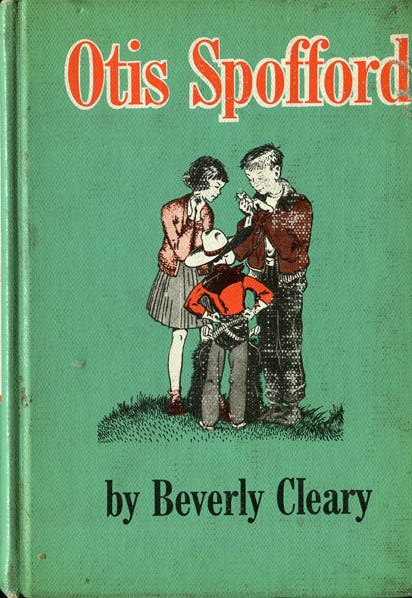

As a kid, I didn’t have a spooky hole in my house like Ramona Quimby, but I understood what it felt like to lie in bed at night, haunted by a scary sound like a plastic sheet flapping like a ghost. There was no Otis Spofford to taunt me during my ballet class, but like Ellen Tebbits, I did know the pain of finding a new friend, then losing her (although Ellen and Austine make up in the end). And although I had no cow of my own to bleach, like Emily Bartlett (of “Emily’s Runaway Imagination”), I spent my childhood rattling around my family’s big old farmhouse, dreaming up weird ways to have fun.

And as a young kid, Cleary’s books for older readers offered me windows into things I hadn’t felt, but was curious about: Jean Jarrett not being sure if the boy she liked really liked her back in “Jean and Johnny”; Jane Purdy’s agony over whether she would look babyish next to the more sophisticated Marcy in “Fifteen”; Barbara MacLane wistfully watching her older sister grow up in “Sister of the Bride.”

Like most of the books I read as a kid, Cleary’s stories described a world I didn’t inhabit — one where your best friend lived next door, the library was just down the street and the sidewalks were your playground. On the farm where I grew up, I had plenty of space to play, but friends, libraries and playgrounds weren’t within walking distance.

But my mom grew up in town — not in Portland, but 100 miles or so south. And she was just the right age to have played with Henry, Beezus and the rest of the gang. When I read the “Ramona” books, it’s easy for me to imagine my mom as a kid playing Brick Factory, stomping around on coffee can stilts, or giving a tongue-lashing to a pair of older bullies. I grew up hearing similar stories from my mom as she described a childhood that seemed to be wonderfully full, rich and free.

So reading Beverly Cleary’s books as an adult — as a mom — is a triple gift. Through these familiar stories, I can now glimpse my own mother as a child: independent but not always wise, strong-willed but also unsure, quick-witted but also a deep well of emotion. I can see with new eyes how her childhood, even with all its freedoms, was rarely carefree, for nearly all children harbor worries and fears.

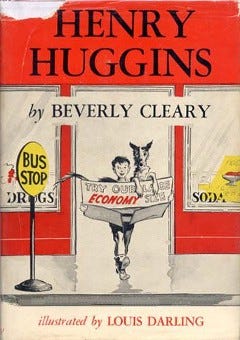

I also see my own childhood self, and can reflect on how complex and how lonely the private lives of children can be — how many inner struggles take place in plain sight as grown-ups calmly fix dinner nearby. It is this complexity that Cleary seems to have always remembered when she wrote about children, treating her subjects with dignity even when they were at their most ridiculous — like Ramona Quimby getting stuck in some very irresistible mud, or Otis Spofford walking home in his ice skates. Remembering this complexity, and the way the demands we place on children can seem confusing, irrational and vexing, has helped me build empathy for my own daughter.

And I saw parenting written on the page in ways I found both deeply familiar and suddenly startling. How strange it seemed to me, sitting in my 8-year-old’s bedroom, deep in the middle of our intricate bedtime routine, to read of Mrs. Quimby calling to ask 8-year-old Ramona to turn off the light and go to sleep. What, I wondered, was I doing? Why wasn’t I in the living room asking my Ramona to turn out her light and go to sleep?

This is the richness that Beverly Cleary’s writing offers. For decades, she illuminated simply and beautifully the currents that rippled softly under the surface of everyday life.

This is the richness that Beverly Cleary’s writing offers. For decades, she illuminated simply and beautifully the currents that rippled softly under the surface of everyday life. The subjects for her writing were not grand in scope, nor were they universal. Rather, her writing was anchored in a very specific time and place, a very specific experience that in many ways grows more unfamiliar all the time (how many of us let our 4-year-old and 9-year-old walk to the public library by themselves?), but remains vital.

Cleary followed so faithfully the writer’s credo to “write what you know” that her characters spring from the page in authentic, memorable detail. Her stories remind me that wonderful storytelling does not require elaborate plots, far-flung locations or unbelievable escapades. Instead, she built some of the greatest stories from the things that were the most familiar and closest at hand.

Ramona Quimby, Henry Huggins, and so many of Cleary’s other characters persist because Cleary knew them so well, and cared for them so much. She brought them to life so faithfully that they have lived alongside generations of children — from my mother, to me, to my daughter.

Last week, we were packing up some of my daughter’s books, choosing which we would keep and which books would go. Among the stacks were paperback copies of the “Ramona” books — many, the same Dell Yearling editions I remembered from my own childhood.

“Keep or go?” I asked her, my hands hovering over the two piles of books.

“Keep,” she replied with certainty. “These are classics.”

One last thing …

I just published my first note on Substack Notes, and would love for you to join me there!

Notes is a new space on Substack for us to share links, short posts, quotes, photos, and more. I plan to use it to connect with you, and with other writers, more often and more easily.

How to join

Head to substack.com/notes or find the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. As a subscriber to Think of the Children, you’ll automatically see my notes. Feel free to like, reply, or share them around!

You can also share notes of your own. I hope this becomes a space where every reader of Think of the Children can share thoughts, ideas, and interesting quotes from the things we're reading on Substack and beyond.

If you encounter any issues, you can always refer to the Notes FAQ for assistance. Looking forward to seeing you there!