'There was no bridge'

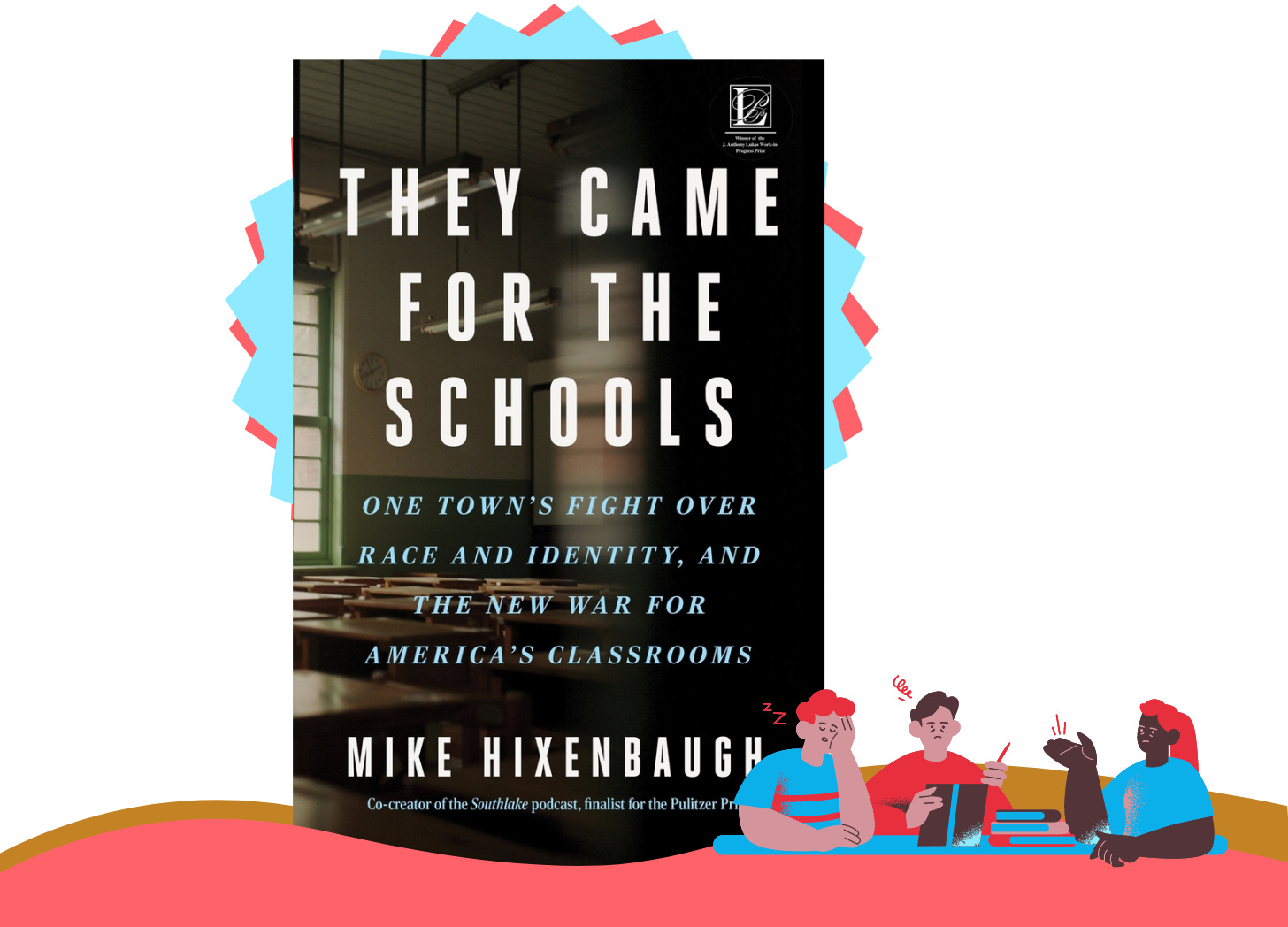

In 'They Came For the Schools,' Mike Hixenbaugh gives a behind-the-scenes look at how national politics around equity tore apart the community of Southlake, Texas.

Mike Hixenbaugh is a senior reporter for NBC News, co-creator of the Southlake podcast, and the author of “They Came for the Schools: One Town's Fight Over Race and Identity, and the New War for America's Classrooms.” His book uses the story of Southlake, Texas, as a lens into a much larger struggle that’s playing out all over the country around race and education. I interviewed Mike about his book, and the challenges of reporting this story.

What was it about this topic that made you want to dig into it further?

Throughout my career, I’ve covered a whole huge range of beats, from education to the military to health care, and the through line has been telling stories of how policy and politics and powerful interests affect the lives of regular people. That’s the same for this project. It is on the surface a story about education, but the schools are really a proxy for something bigger. The book is about things like who we are as a country and how toxic and divisive political tactics that have trickled down from the national level are disrupting and upending people’s lives.

In my suburban Houston neighborhood, which is this sleepy little subdivision where nothing happens, I was seeing these really ugly fights play out on the neighborhood Facebook page and in people’s yards. There were these claims that Antifa was going to come and shoot up our neighborhood, things like that. It was all really stressful for my wife, who’s a Black biracial woman, and that’s going to make the connection to why I dug into this.

In the midst of all this backlash against Black Lives Matter, she put up a Black Lives Matter sign in our yard, and it resulted in this kind of repeated attack on our property. Every weekend someone would drive their four-wheeler into the yard and turf the yard up. It sounds like a small thing, but it felt so personal to me. And I found my wife crying one day after a walk in the neighborhood, saying, “I don’t want to live here anymore.” That was kind of what propelled me to start reporting on this.

I found my wife crying one day after a walk in the neighborhood,

saying, “I don’t want to live here anymore.” That was kind of what

propelled me to start reporting on this.

And throughout my reporting, I was hearing the same thing from other people – from parents of LGBTQ kids, from Black parents, from educators – who built their lives around a suburb or a school system and all of a sudden were feeling unwelcome, unwanted, unsafe in their communities. It was all tied to this backlash against how schools were working to address discrimination and racism.

I centered the story on how kids, parents and teachers were living with the consequences, to show people that, maybe it seems harmless. It’s just words. You’re going on social media or showing up at a board meeting. Well, those accusations have a big impact and it can upend people’s lives.

When did you know that this was something big — that this wasn’t just a simple story, but that there was more here?

I started doing my initial reporting over the fight on the diversity plan in Southlake in late 2020, early 2021. And I went into it with a hunch that this was emblematic of a much bigger thing happening in other places, but this was before we started hearing the phrase critical race theory, it was before school board meetings were making national news, so I set out to tell the story of how this fight over big nationals thing was rippling through this local community in a big intense way.

I reported it with a colleague named Antonia Hylton who produced a piece for NBC Nightly News, and after we ran those stories, that’s when we knew that this was bigger. We started getting flooded with emails from people who were saying, The story you told in Southlake, that’s the story in my suburb, the same thing is happening here. We get dozens of these emails, and I think we realized we were on the leading edge of something.

As you began to report on what had happened in Southlake, what surprised you? Was there anything that was different than what you expected to find?

I was surprised, and maybe I shouldn’t have been, by how entrenched people were in their position. Particularly people who were kind of spreading false or distorted information about what was happening in schools. I thought if we did some very in-depth reporting, which I’ve now vastly expanded on in the book, and helped people hear the voices of people just reacting to the world around them, that it would take some of the tension down.

I was talking to parents of Black children describing a very emotional experience in a very poignant way that would make any person feel empathy. And on the other side, there were people coming to school board meetings talking about a leftist takeover and a plot to indoctrinate white children to hate themselves and hate America. But that’s like two different realities.

I thought if I could let people hear the perspectives of the parents and the students, and then sit down with the people who were angry, that it would clear some things up.

I thought if I could let people hear the perspectives of the parents and the students, and then sit down with the people who were angry, that it would clear some things up.

But that was the other thing, was that from the beginning, those folks would not speak to me. Leaders in the community put out the word, Don’t speak to them. That surprised me too. Fortunately, these folks did a lot of talking in public.

But the idea that if I could just tell the story of how these parents were feeling and how their kids were feeling, that it would take the tension down and we could at least agree that kids shouldn’t be hearing racist jokes or the N-word — the response wasn’t that. What I got instead was, You’re lying, that’s not real, you’re exaggerating, that person’s trying to tear us down. There was no bridge.

So what is it that you hope people will take away from this, if you’ve realized you’re not going to convince some of those who are entrenched in their opinions?

I think there's huge value in telling these stories. There are people whose position softened or they have developed empathy for people after listening and reading. They’re not as loud as the angry folks, but those people exist.

And also I’ve heard so much from teachers and parents and kids who have just said, I feel less alone because I’ve read what happened in that case and I see my story reflected in it. And that’s good, that’s a really good thing. That’s not changing anyone’s minds but it is putting a little bit of goodness into the world.

What was challenging about reporting this story?

Reporting on schools is challenging in general. It’s not like covering city hall where you can just walk in and pop in and knock on a door. I used to cover the military, and covering schools is a lot like that. You’ve got to get face access. You’ve got to get permission to go see what’s happening inside. Then you add this layer of coming to write about a very divisive political fight that’s tearing your community apart? No one was letting us in.

Finding people and students to talk about their experiences, winning their trust, was very challenging. And getting a full picture of what was happening in schools was challenging. I ended up relying a lot on secret audio recordings. It’s amazing — students will just hit record on their phones when something’s happening, and it’s like this amazing window into seeing and hearing things that I could never get. It’s more authentic and real because a journalist’s presence changes things.

Looking back on what happened in Southlake, do you think there’s anything anyone could have done differently to change the outcome?

One thing that I’ve been thinking about is the fact that schools were, all over the country, having their own racial reckonings before 2020. That’s what happened in Southlake. During this time period from 2017 to 2020, I found just case after case after case where some racist incident got a lot of attention, and that became an impetus for other families and parents to come forward and say, Actually, this is not just this incident, it’s a whole culture, I’ve been living with it, it hurts, you don’t know what it’s like to have kids tease you about these things. But from 2017 to 2020, that didn’t get the same level of coverage nationally or regionally or even locally as the kind of anti-CRT blowback and backlash that followed. So I just think that, as journalists, we missed that.

There could have been some big, comprehensive reporting on it, because the story was kind of just out there in plain sight. There was a whole moment of suburban schools reckoning with their legacy in a really big way, and it was happening in lots of places. And to bring it back to Southlake, the school leaders didn’t necessarily do as good of a job as they could have to fully communicate what was happening to everyone in the community.

By the time 2020 came along, lots of parents, especially white parents, didn’t know that there had even been this reckoning and didn’t know what was happening. So when they found out about a plan to address those things, they were hearing it in the context of 2020 and all the protests. And there was no going back.

I think communities need to communicate really well, and journalists should be on the lookout for these kinds of stories.

You can find Mike Hixenbaugh’s work and his social media at mikehixenbaugh.com.

Maybe don’t put out a sign in support of a terrorist group.