The Death and Life of a Two-Room Schoolhouse

The casualties of centralization and the myth of local control

My old elementary school is for sale. You can buy the 4,000-square-foot, midcentury Oak Grove Elementary School building in scenic Polk County, Oregon, for $750,000, complete with vintage chalk boards, in-room drinking fountains and tiny, child-size toilets.

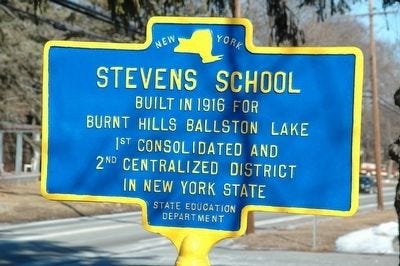

On the face of it, there’s nothing unusual about this sale at all. The school been closed for almost 20 years, and old schoolhouses go up for sale all the time. Especially here in upstate New York, where the centralization movement dropped the number of public school districts from upwards of 9,000 to just under 600 during the 20th century. Centralization continues, even now, though haltingly, as declining enrollments in upstate New York push districts to consider merging their already-centralized districts into even bigger consolidations.

Centralization happened in Oregon, too. Although it wasn’t until 1991 that the state Legislature required all school districts to become K-12 districts, many small local schools had already been replaced with, or subsumed into, central school districts, just like in New York. Today, many of those former country and village schools house apartments, private homes, churches and restaurants. Others stand vacant, like Oak Grove does.

Even though Oak Grove Elementary has been closed for almost 20 years, it still gives me a weird pang to see it listed for sale. It looks so … vulnerable? I guess this is a little piece of what it looks like to see your childhood home listed for sale, because I feel fiercely protective of this old building, with its boarded-up front doors, its low-ceilinged basement (complete with duct-tape covered pole where we used to have P.E. on rainy days), and its bright, high-ceilinged classrooms.

I could write thousands of words about my elementary school. I delight in telling stories about what it was like to attend a two-room schoolhouse with a handful of other kids. I can rattle off all the things we didn’t have: no cafeteria, no principal in the building, no nurse’s office, no gym. Our library was a bookshelf in the basement. We ate lunch at our desks. Our teachers managed, somehow, to instruct multiple grades, all in the same room, all at the same time. In first grade there were about 30 of us in one room spanning first through fifth grade. The next year they hired another teacher and we got split up, but after that I had the same teacher for three years running. Just her and us. No aides, no office staff. If the phone rang, she answered it.

When I look at the photos in the real estate listing, it all comes flooding back. The heavy front door that unlatched with a satisfying “click.” The tall shelves in the hallway where we set our lunch boxes in the morning. The cupboards under the sink in our classroom where we germinated pea plants and watched to see what would happen if they tried to grow in darkness. (they stretched palely upward toward the tiny crack of light that snuck in past the cabinet door, leggy and hopeful.) The textbook storage room next to the bathrooms, where I would sneak in to read beloved passages from the previous year’s reader (the blue one with the triceratops on the cover).

I was going to write that there’s nothing particularly special about my old elementary school; that it just feels special because it was mine.

A lot of things look different, though. The classrooms and basement are tagged with graffiti. The front door windows are boarded up. Rust streams down the wall from a basement window. The chalk boards are still there (one classroom even has a falling-down strip of cursive handwriting letters above the board), but everything else that gave the rooms color and life, except the brick-red Venetian blinds, is gone. The playground equipment has been removed. The lines painted on the blacktop for playground games have faded. The tetherball pole hangs askew, rusted. The baseball backstop has come down, but the trees that my dad planted at the school when I was in the second or third grade have grown tall, and look beautiful.

I was going to write that there’s nothing particularly special about my old elementary school; that it just feels special because it was mine. But Oak Grove Elementary actually was quite special. It was a neighborhood school out in the country, a rare blessing for farm kids who, for those five years, got to ride the bus for only a couple minutes instead of several miles. It was a throwback to a small and simple setting that demanded differentiation and collaboration across grade levels. It was a holdout against pressures to put kids into bigger buildings with a more standardized program, in part because the parents whose kids went to Oak Grove loved it fiercely. I loved it fiercely too, in no small part because I felt sure that it loved me back.

“Today we are in a new age, an age of rapid transportation and communication with automobiles, airplanes, radio, radar and television as vehicles to carry on our activities in a modern world. We cannot solve our problems in terms of our own little community alone. For the individual, his whole mode of living has changed from that of a generation ago. Peoples across the seas, in many respects, are as close to him as were those living in the adjoining county in the days of our parents and grandparents. As a result we do not live the same, think or talk as they did, and our necessities for this modern age far exceed those of ‘the good old days.’”

— CONSOLIDATION OF SELECTED SCHOOL DISTRICTS IN CENTRAL POLK COUNTY, OREGON,” Carl Morrison (graduate thesis), 1953

Announcing the closure of Oak Grove Elementary in April 2003, the school superintendent pointed to a loss of local control over revenues as a deciding factor in the closures. (Nearby Eola School, a one-room schoolhouse that at the time housed an alternative school program, was also closed at this time.)

"People come to us as if schools were still under local control. That's been lost by districts and parents,” Superintendent Forrest Bell told the Polk County Itemizer-Observer in 2003. “Budget committee and board have no say over the revenue. The revenue is set at the state level."

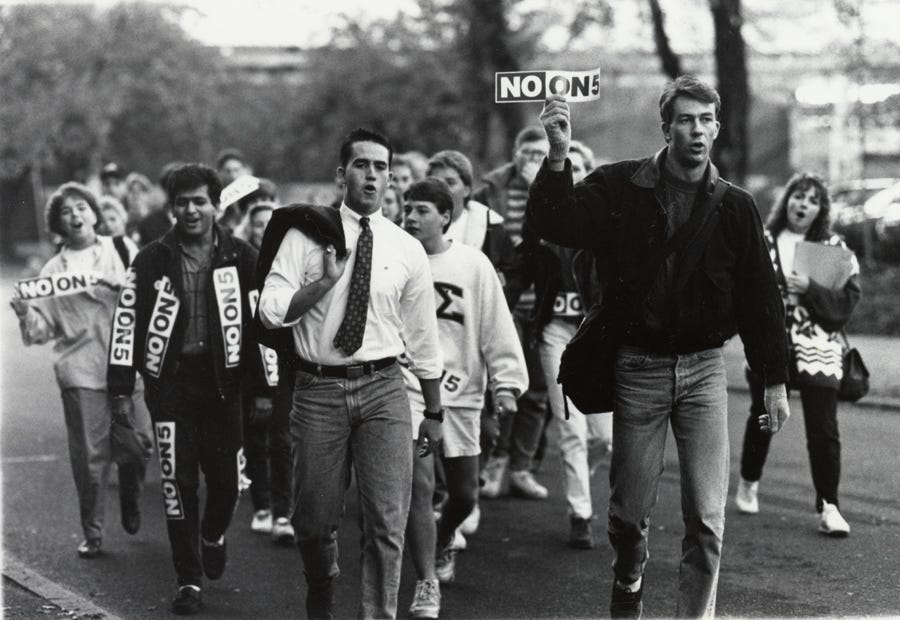

This shift away from local control for Oregon’s public schools was a long, back-and-forth process, but most point to Measure 5, passed by voters in 1990, as a foundational shift in how the district would fund its education system. The ballot measure limited basic local school property taxes to one-half percent, or $5 per $1,000 assessed value, in an effort to stem runaway property tax increases. This had the effect of making many school districts more reliant on state funding (rather than local funds).

It is ironic, in a way, that Measure 5 was championed by conservatives, when the measure has resulted in less local control and more state control over public schools. I was still a kid when Measure 5 passed, and didn’t pay much attention or understand it at the time, but in the years that followed, I heard its name invoked often as a turning point for schools. Its effects are still being felt today.

Superintendent Bell told the Polk County paper in 2003 that the state Legislature decided how much money the district would get, and it lacked the power to raise revenues. At that time, 85% of the district’s funds went to contractual obligations, leaving little room to maneuver.

About a decade after Oak Grove Elementary shut its doors, New York state took its own action to limit rising property taxes — and, subsequently, tamp down school spending. But, somewhat surprisingly for a state that loves its bureaucracy, the state did not follow Oregon’s path of turning school spending control over to the legislature. Instead, the state put in place what is frustratingly referred to as a 2% tax cap, even though it is not really any of these things. This threatens to get boring, but what I will say about the cap is that it requires school districts to obtain a supermajority (60% plus 1 vote) approval for any proposed budget that exceeds the district’s property tax levy limit, which changes every year and is governed by a complex set of factors.

The key difference here — which was never the case in Oregon — is that New York voters cast ballots directly on their local school district’s budget every year (except in the “Big 5” districts of Buffalo, New York City, Rochester, Syracuse, Yonkers, Albany, Mount Vernon and Utica1). This is unlike any other budgeting process in the state; typically elected officials make budget decisions. But not with New York schools.

So local control in New York is alive and well, at least in theory — but the property tax cap, also, has done its job at limiting the amount of local revenue that schools are raising. While districts can exceed their tax levy limit and hope a supermajority of voters turns out, the cap has had a chilling effect, and few school boards are willing to take the risk. And “local control” can only go so far when school districts face an ever-increasing list of unfunded mandates — especially for small, rural schools.

Sometimes I wonder if Oak Grove Elementary’s fate would have been different if Measure 5 hadn’t passed. If Oregon had found some other way to balance the burden on taxpayers with the need to still actually fund education. It is astonishing to me that, one year after Measure 5 essentially cut school funding off at the knees, the state passed legislation “calling for major changes in school programs aimed at making Oregon students the best educated by 2000 and a workforce equal to any in the world by 2010,” according to the Oregon School Boards Association. How would this goal be achieved without funding to support it? It makes me wonder, as I often do, “What are we willing to do to get the things we say we want?”

When I saw the real estate listing for my old elementary school, I immediately posted it to a Facebook group that I had set up, years ago, for Oak Grove alumni. “Anyone got $750,000 laying around for a good cause?” I asked.

The school district still owns the property, and I don’t know exactly why it’s being sold now. Probably because they need the money. Probably because whatever magic everyone was hoping would happen — someone swooping in with money, with grant funding, with a new plan that could sustain this old country school — never did.

I wish I had that magic. I wish I had $750,000 and a plan. I wish that some kid, some day, could pull open the heavy front door of Oak Grove Elementary and see the mural painted above the basement stairs.

Oak Grove wasn’t perfect; there were a lot of things it couldn’t do. A lot of IEPs would have been hard or even impossible to implement in such a small learning environment. There were steps and no ramps. There was nowhere to take a child who was having a hard time and might need to step away from class for a minute, or for longer. Nowhere to ask a sick child to wait to be picked up if they needed to go home. It was limited, and it wasn’t better than other schools. But it was mine. It was ours. It had a lot to offer — to me, to my family, to other kids and families in the community. And it’s sad to see it all end this way — a boarded-up building littered with graffiti where kids once laughed, learned and played. I wish things could have gone differently, but it seems as though it’s far too late.

Yes, that’s more than five schools; no, I don’t know why there are more than five schools in the “Big 5” ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

This is terrific, heartbreaking, thought provoking.